Recently, someone asked me the question I’ve heard many times before:

“Do Vodou dolls really exist?”

My short answer? Not really. At least, not the way movies or Halloween decorations would have you believe.

But the longer answer is much more complex—and filled with cultural distortion and even radiology scans of alleged Vodou dolls found in a Haitian cemetery.

Let´s see if we can unpack this subject.

Forget the tourist traps

To avoid falling into the clichés of pop occultism, I’ll base this discussion on academic sources. And no, TikTok users and Instagram accounts are not the best sources.

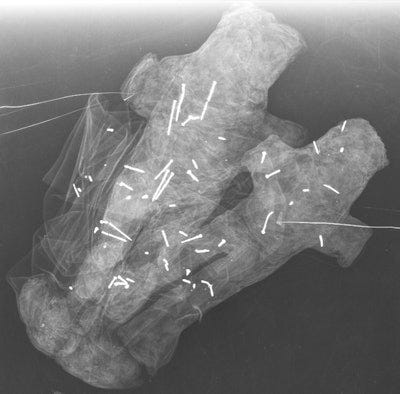

For example, a curious forensic radiology article by Agias et al showed a collection of “dolls” that was retrieved from a cemetery in Port-au-Prince and subjected to X-ray examinations, revealing that dolls are used in Vodou. And yes, some of them contained pins/nails. So, how do we unveil the meaning of this? Let´s proceed a little bit further before returning to those dolls found in this graveyard.

It is important to state that I’m grateful to Professor Dr. Manbo Kyrah Malika Daniels, whose guidance brought these pieces to my attention.

Figurative Magic: From Europe to Africa

Natalie Armitage, in another very good study, points out something critical: the idea that “like affects like” is a widespread magical principle. You see this in the use of human-shaped figures in both ancient and modern magical rituals, especially in Ancient Egypt and Europe.

In Europe, these practices were often branded as witchcraft, plain and simple. But in West Africa, things were very different. Magic wasn’t seen as an unnatural thing, it was often part of everyday life. Armitage writes:

“Unlike in Europe, where magic was superstitious, against God’s will and, at its worst, positioned in the realms of the Satanic, magical practice in many West African cultures at the time was situated quite differently within their society.”

Fetishes, Nkisi, and Nails

Let’s talk about fetishes—not in the Freudian sense, but in the colonial one. The word comes from the Portuguese feitiço, referring to an object believed to hold magical power. To European eyes, these objects were false idols. But to Africans, they were legitimate spiritual tools.

One key example is the nkisi nkondi: a container of spiritual force, often crafted in human form. Some nkisi are pierced with nails or blades—a striking image, suspiciously similar to the so-called Vodou doll.

To the European mind, those nails screamed “curse” or “black magic.” But in context, they were more often offerings, thank-you gestures, or ways to activate the spirit within the object.

Armitage even suggests that the practice of hammering nails into nkisi might have been influenced by Christian iconography—specifically, the image of Christ nailed to the cross.

So Where Did the Vodou Doll Come From?

Armitage concludes—and I agree—that the image of the pin-stuck Vodou doll didn’t come from Africa at all. It’s far more likely to have originated in European figurative magic, which then got projected onto African and Afro-Caribbean practices through colonial misunderstanding.

But there’s another chapter in this story, one that involves toxic dolls, American colonialism, and profound misunderstanding.

The curse of the cashew dolls

Scholar Sara A. Rich states that Vodou dolls do not exist.

She then recounts a strange episode during the American occupation of Haiti, when handmade dolls—crafted from cashew shells—were exported to the U.S. as exotic souvenirs.

The problem was that the health authorities thought the cashew parts were toxic. They believed that children who chewed on them became severely ill, and in some tragic cases, died.

The U.S. government issued a dramatic public health warning, banning Haitian dolls. What followed was a witch hunt.

It’s not a long leap from “toxic Haitian dolls” to “dangerous Vodou magic.”

It’s the same kind of logic that brought us Brazil’s famous urban legend of the “Fofão doll” with a knife hidden inside. (If you’re too young to remember or not from Brazil, Google it—you’ll see what I mean.)

Do Vodou dolls dream of Hollywood?

So, do human-shaped dolls appear in Vodou? Yes, sometimes. But not the way Hollywood says. As usual, the cinema industry has a way of twisting the truth.

They are rare, and when used, they’re typically for healing, love rituals, or communicating with the dead, not for causing harm. Karen McCarthy Brown, a respected Vodou scholar, backs this up.

Thus, those dolls found in the cemetery and submitted to x-ray scans in the study by Agias et al. Maybe the pins were for activating the spirits, or maybe, and this is important, some people did use pins in dolls to try to make some evil.

First, it is important to understand that in Vodou, cemeteries aren’t spooky or cursed. They are places of deep magic and healing. Something found in a cemetery isn’t automatically sinister.

But the expansion of those Hollywood myths about Vodou led some ill-intentioned people, in Haiti included, to pretend that those dolls are a legitimate part of the Haitian Vodou practice in order to gain money from tourists or gullible people.

Vodou, Sensationalism, and Spiritual Colonialism

Let me be perfectly clear:

There are Haitians who make dolls meant to harm. Just as there are exploiters and charlatans in every spiritual tradition. But that doesn’t make the pin-stuck doll an authentic, central part of Vodou.

It’s more accurate to say that the Western imagination invented the Vodou doll, then exported it globally, eventually influencing Vodou itself. This is what colonialism does: it imposes a distorted narrative, and sometimes that narrative is internalized by the very cultures it misrepresents.

What Vodou Is Not

Let’s not paint Vodou as all light and love—it has a combative side, like any rich spiritual tradition. There are rituals for justice, for defense, even for revenge.

But the image of a doll stuck with pins to harm someone?

That is not Vodou.

Vodou is not about vengeance through voodoo dolls. It is not horror movie material. It is a complex, beautiful, and often misunderstood spiritual path—one that deserves better than cartoon villains and tabloid superstition.

Notes & References:

Augias et al., Haitian Voodoo Dolls Revealed by X-ray: From Radiology to Medical Anthropology. Journal of Forensic Radiology and Imaging, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 221–225.

Sara A. Rich, “The Face of ‘Lafwa’: Vodou & Ancient Figurines Defy Human Destiny,” Journal of Haitian Studies (2009): 262–278;

Natalie Armitage, “European and African Figural Ritual Magic: The Beginnings of the Voodoo Doll Myth,” in The Materiality of Magic (Oxford: Oxbow, 2015), pp. 85–101.

Nkisi are power containers in Central African spiritual systems, often associated with the Kongo cosmology.

Many people confuse Haitian Vodou with Hoodoo and New Orleans Vodou—distinct systems. For clarity, see Vodu, Voodoo e Hoodoo: A Magia do Caribe e o Império de Marie Laveau by Diamantino Trindade and Sebastién de La Croix (Arole Cultural).